Juan Carlos Verme is an entrepreneur and investor, as well as an eminent private collector of contemporary art and an active participant in educational and cultural projects in Lima, Peru and across Latin America.

He has been Director of the Board of the Museo de Arte de Lima (MALI) since 2005. In addition to his presidency at MALI, Verme also participates in the museum’s Contemporary Art Acquisitions Committee and the Formando Colecciones (Building Collections) programme. Verme was Board Member, Treasurer and Vice President of the Asociación Cultural Filarmonía, a cultural initiative dedicated to promoting philharmonic classical music through radio.

Since working with Asociación Cultural Filarmonía, Verme has directed and hosted the radio programme ‘Mi Oído Izquierdo (My Left Ear)’. Verme also belongs to the Board of Tate Americas Foundation and is a member of the acquisitions committee of African and Latin American Art. Since 2012 he has served as Vice President of the Fundación Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid, Spain. This year, Verme became involved with Proyecto Amil – a mobile and non-commercial contemporary art project based in Lima. ‘Proyecto Amil’ is dedicated to fostering less conventional art practices in the local area and bridging the gap between this work and the international community.

Here Juan Carlos speaks to Marc Payot, Partner and Vice President of Hauser & Wirth, about the history and highlights of his collection, and the role of institutions in fostering cultural understanding.

Marc Payot: I thought we could start at the very beginning of your collecting story. How did you begin collecting? What was the first work you ever purchased?

Juan Carlos Verme: The two first art pieces I bought were both prints by Joan Miró. It was in Zurich in the year 1985, I had just turned 21 and had recently moved there from a rigorous boarding school in Central Switzerland to study psychology at the local university. My mother had given me some money to buy a bed and a few pieces of furniture, but instead I purchased these two artworks that I put on the floor of my rented apartment, next to my lonely mattress. The pieces depict scenes of a human shape –probably a girl – in a landscape and, the other one, a night sky with stars, in the artist’s mid-career fashion; nothing that I would find compelling these days. Two or so years earlier, I had visited a Miró show at the Kunsthaus in Zurich and I had become a fan of his work. I remember one painting in particular that called my attention and devotion – it was an early one called ‘The Farm’ (1921 – 1922). But I was also taken by his more late work. His quest into the reduction of form, and later into abstraction, appealed to me; as did the colours he used, and of course, his way of drawing with the brush, reminiscent of oriental calligraphy.

MP: How do you collect? What choices do you make before deciding to acquire an artwork? Do you bear the rest of your collection in mind when approaching a new piece – in other words, do you consciously look for your collection to have a certain coherence, or do you make choices based solely on the merit of each individual work or artist?

JCV: First, I work hard to earn the money. Then – as they say – I collect. Coherence and surprise are two elements that go together in the process of making a choice – like a master and his or her dog on a leash taking a stroll.

Sometimes one leads, sometimes the other paces ahead. But at the end of the journey they probably arrive together. Of course I have in mind what makes up the bulk of the collection, but I don’t have all the possible readings of such a corpus at any given time – those readings or additional meanings are also expanded when I look at new works by artists that were not known to me before. My learning and my experiences also reshape how I see art and how I perceive it; therefore it affects what and how I look at art, and eventually, what I may wish to acquire.

As you know, I have been buying drawings by Roni Horn over the years. That makes one body of work in my mind. And I will continue to want to see – and possibly buy – her new work when it comes out of the studio. On the other hand, I go through epiphanies such as the discovery of work by artists like Jean-Luc Moulène and Nancy Spero – both seen in one single show at Punta della Dogana in Venice lately– that I had never heard of or seen before. Then, if it is possible and if I find the work available, I buy it without asking myself how such works will affect what is already there, at home. For one way or another, they will make sense, either because they go deeper into an existing field or subject matter, or because they open new avenues of thought and comprehension.

The art collection, as I see it, is by nature always unfinished. Collecting is a process, an intellectual and emotional journey and it is a vehicle for learning purposes. It is a means of coming to know people and their ideas; it is a way to try to grasp humanity, and it can help to make some sense of the world, by acting as a catalyst for questions. It is a tool to get to know how others perceive life on earth and it is also a quest for contemplation and introspection. Last but not least – and very important aspect for me – it is an infinite source of pleasure and joy (I shall remind you, that I mentioned the suffering attached to it in the very beginning of this paragraph).

In another realm, I am part of four different museum purchasing groups. Buying art for museum collections is a quite different thing altogether...

MP: That was put so beautifully, thank you. We will talk about your involvement with museums later, as it’s something I think is important. But let’s stick for a moment with collecting in depth. You mentioned Roni Horn. What triggers you to collect an artist in depth?

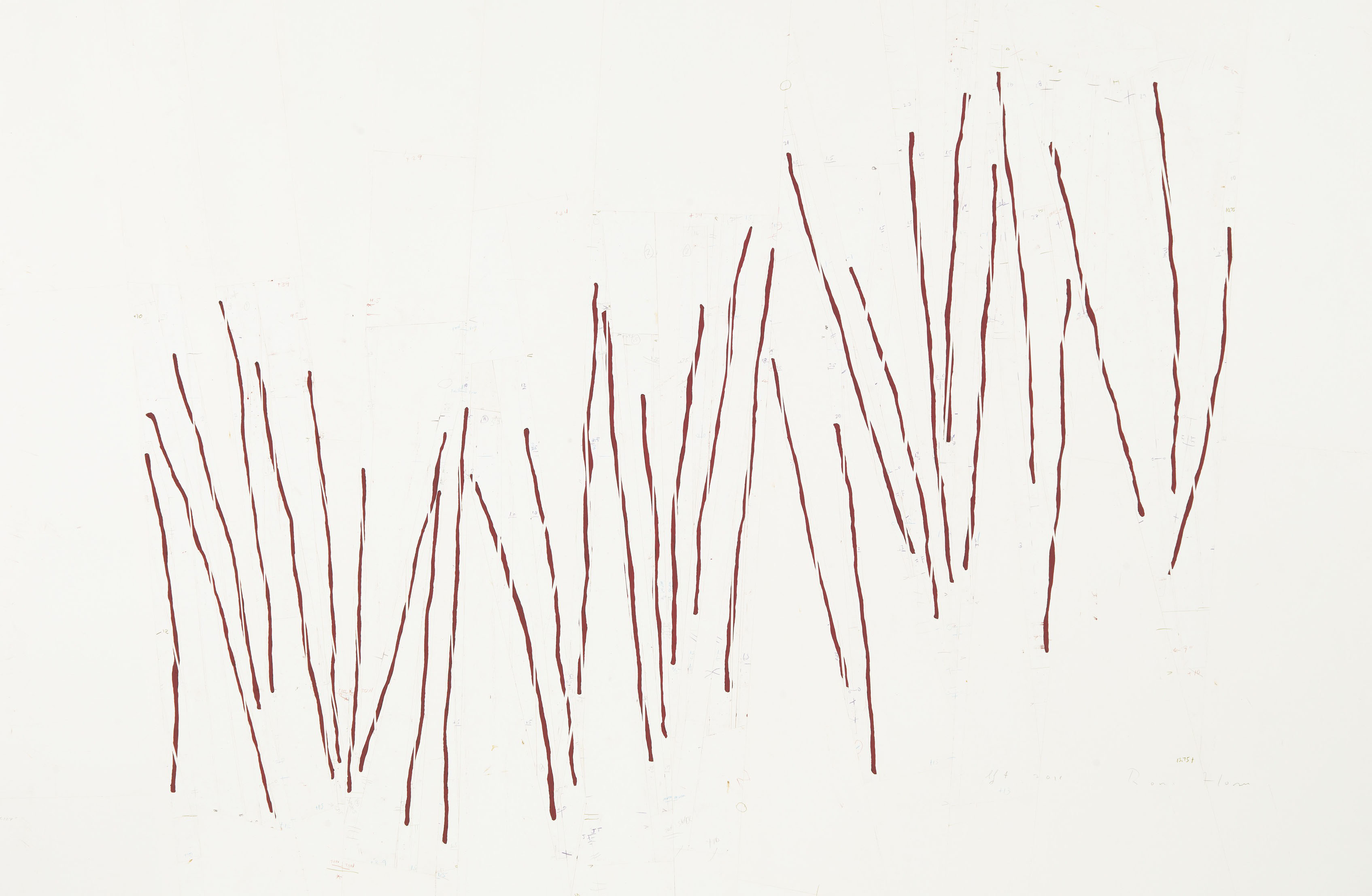

JCV: If I discover a profound affinity between the artist’s work and my own quest for meaning, then a moment of epiphany follows; such a state of mind and emotion entices me to follow her or his work. In Roni’s case, I cherish her work very much as a whole, but it is her drawings specifically that bring me close to a state of nirvana on earth, that I otherwise fail to achieve through meditation or orgasm. [Laughs.]

An element that needs to be present for me in a work of art is an inherent density or quality to take the observer somewhere else: further, beyond the unknown, beyond the familiar – to put you in contact with the Other.

MP: I understand. And on a related note, is it important for you to know the artist personally? Does having a relationship with an artist affect your relationship with their work in any way?

JCV: Look, there are great artists that have difficult personas, and there are great ones that are sublime to spend time with. It does have an effect on me, but not on the artwork. Yes, I definitely prefer to have a good relationship with the artist, but it is not a pre-condition to enjoy the work –neither to acquire it – by any means.

MP: What you say about collecting artists in depth is very interesting. It’s definitely true that personality does not correlate with the quality of an artwork. I know that your relationship to museums is important to you. You are on the board of several international museums. Why is this important to you, and in what sense does it extend your involvement with contemporary art?

JCV: Collectors should feel the urgency to act towards a common cause and should put themselves at service of their local museums – and their favourite ones. This implies having less private or family museums, which are, with few exceptions, a shot in the wrong direction, unless your last name is Frick or Moreau. I have been repeating this mantra for a long time. Apart from MALI in Lima, of which I have been a Trustee since the age of 33, I have been involved with Tate Modern through the Latin American Acquisitions Committee and as a Trustee of the Tate Americas Foundation. A few years ago, I became involved in the newly created Foundation connected to the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid, of which I serve as its Vice-Chairman of the Board. Last but not least, there is Proyecto AMIL, an art platform in Lima devoted to less conventional art practices. Proyecto AMIL acts as an enabler of artistic ideas, publications, residencies, commissions and other things too. This is, for the moment, a more personal project in conjunction with Joel Yoss.

These duties and responsibilities are very important to me because they allow me to serve the local community – in the case of Lima and Peru – and also to be in contact with a wider audience – as through the two metropolitan museums. It also provides a service to the artists and their work in those geographical or cultural spheres. An art museum is, among other things, a platform that brings the public into contact with the work and the ideas of a virtual ensemble of artists. In the case of the contemporary museum, as in a Kunsthalle, you bring together the work of living artist for a public that feels the need to see and experience what these artists think, feel and choose to do.

Of course, all this activity puts me in contact with more and, perhaps the most interesting, artists. And more. It is a vehicle to meet other collectors, curators, gallerists and cultural agents at large, and to enter in a genuine dialogue with them. It is a phenomenal way to enlarge and enhance your circle of human beings. I have got to know so many beautiful people through this exercise, and I have come across a few really outstanding ones. I have been exposed to their ideas and I have seen the results of their constructive struggle. I feel so happy to be surrounded by so much talent and humanity! It’s the best thing that has happened to me outside the four walls of my home...

MP: Wow. On a related note, I would love to discuss your relationship to the Lima Museum of Art (MALI). What is the significance of this museum for you? Especially considering that you live in Lima and that it is not one of the major cities for contemporary art.

JCV: This is a very simple question for me to answer. The significance of MALI to me is hefty. It all started in the nineteenth century when a great grandparent of mine came from Lugano in Switzerland to work as a specialist craftsman in the plaster works that are in abundance on the walls inside the building and on its façade. But that is the longer version of the answer...

Let me try to be brief but perhaps more eloquent. I felt that I wanted to belong to MALI because I recognised that there were a group of enthusiastic people with a transcendent mission at work there. The mission was – and is – to bring the magnificent art of the people who have inhabited the territory known today as Peru throughout three thousand years or more to the wider public. Keeping that art properly stored for future generations was simply not good enough for me and other members of this team. We are committed to showing a truly encyclopedic account of Peruvian art in a meaningful way. On another note entirely, we also wanted to provide Limeños with a good view of what was, in artistic terms, happening outside the city limits.

Following extensive renovation work, the second floor is now open (4500 sq metres). The collection consists of 17,000 pieces of Peruvian art from all times and in all media, from textiles to video, and from objects in gold and silver to plastic.

MP: What an incredible mission statement. I’d like to return now to your collection. And I have two questions– is there a work that epitomises the point where all your key interests converge? What are these themes?

JCV: Good question! You are asking me whether there is a Gesamtkunstwerk in my collection... [Laughs.) I can respond with many examples, not just one. Among those examples, there is a work by a Peruvian artist named Morros Moncloa; a work produced in the late fifies. It is a painting, an acrylic on agglomerate wood, and its size is rather big (something like 80cm x 160cm). It is a geometric abstraction, painted in very lively colours, of which Canary yellow predominates.

The shapes in the composition are reminiscent of pre-Columbian geometrical abstraction as found in ancient textiles. But the grammar, the syntax of the forms, is very much a particular language developed by the artist. A work very characteristic of Morros. When Cuauhtémoc Medina, at the time curator for Latin American art at Tate Modern, saw it in my office, he exclaimed: ‘...this is Inca Pop!’ Since then, we’ve called it by that name.

It is a work that speaks directly to my nerve. This often happens to me with art that is so powerful – I cannot explain why it is so special. Or is it that I prefer not to talk about it? As if by doing so, I could break the spell that holds me in its grip? It just leaves me speechless. Sorry to disappoint you, this is an interview after all [laughs].

MP: Can you talk about a work in your collection that has a particularly interesting back story? Such as where or how you acquired it?

JCV: You are looking for anecdotes now. I still remember vividly, the thrill I felt when Hester van Roijn bought that Swiss Piece by Donald Judd in a London auction house for me and I was sitting behind her – all because I did not happen to have a paddle.

Of all things material on this world, the thing I regret not beig able to acquire the most is, by far, Donald Judd’s ‘Eichholtern’ (XXXX) on Lake Lucerne in Switzerland. Do you know the site? It was a house, a former restaurant, which Judd transformed into a magnificent piece of perfection by intervening with floors, ceilings, and by knocking down walls and transforming it into a kind of Manhattan-Loft-cum-Swiss-country-house. I was going to purchse it together with a brother of mine and a friend, but as they both dropped out I was left to face a price that was impossible for me at that time. We lost the deal and the house was sold to someone that actually destroyed Judd’s work and converted it into a neo-baroque mansion with no taste or concept. Tragic, isn’t it?

Juan Carlos Verme is an entrepreneur and investor, as well as an eminent private collector of contemporary art and an active participant in educational and cultural projects in Lima, Peru and across Latin America.

He has been Director of the Board of the Museo de Arte de Lima (MALI) since 2005. In addition to his presidency at MALI, Verme also participates in the museum’s Contemporary Art Acquisitions Committee and the Formando Colecciones (Building Collections) programme. Verme was Board Member, Treasurer and Vice President of the Asociación Cultural Filarmonía, a cultural initiative dedicated to promoting philharmonic classical music through radio.

Since working with Asociación Cultural Filarmonía, Verme has directed and hosted the radio programme ‘Mi Oído Izquierdo (My Left Ear)’. Verme also belongs to the Board of Tate Americas Foundation and is a member of the acquisitions committee of African and Latin American Art. Since 2012 he has served as Vice President of the Fundación Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid, Spain. This year, Verme became involved with Proyecto Amil – a mobile and non-commercial contemporary art project based in Lima. ‘Proyecto Amil’ is dedicated to fostering less conventional art practices in the local area and bridging the gap between this work and the international community.

Here Juan Carlos speaks to Marc Payot, Partner and Vice President of Hauser & Wirth, about the history and highlights of his collection, and the role of institutions in fostering cultural understanding.

Marc Payot: I thought we could start at the very beginning of your collecting story. How did you begin collecting? What was the first work you ever purchased?

Juan Carlos Verme: The two first art pieces I bought were both prints by Joan Miró. It was in Zurich in the year 1985, I had just turned 21 and had recently moved there from a rigorous boarding school in Central Switzerland to study psychology at the local university. My mother had given me some money to buy a bed and a few pieces of furniture, but instead I purchased these two artworks that I put on the floor of my rented apartment, next to my lonely mattress. The pieces depict scenes of a human shape –probably a girl – in a landscape and, the other one, a night sky with stars, in the artist’s mid-career fashion; nothing that I would find compelling these days. Two or so years earlier, I had visited a Miró show at the Kunsthaus in Zurich and I had become a fan of his work. I remember one painting in particular that called my attention and devotion – it was an early one called ‘The Farm’ (1921 – 1922). But I was also taken by his more late work. His quest into the reduction of form, and later into abstraction, appealed to me; as did the colours he used, and of course, his way of drawing with the brush, reminiscent of oriental calligraphy.

MP: How do you collect? What choices do you make before deciding to acquire an artwork? Do you bear the rest of your collection in mind when approaching a new piece – in other words, do you consciously look for your collection to have a certain coherence, or do you make choices based solely on the merit of each individual work or artist?

JCV: First, I work hard to earn the money. Then – as they say – I collect. Coherence and surprise are two elements that go together in the process of making a choice – like a master and his or her dog on a leash taking a stroll.

Sometimes one leads, sometimes the other paces ahead. But at the end of the journey they probably arrive together. Of course I have in mind what makes up the bulk of the collection, but I don’t have all the possible readings of such a corpus at any given time – those readings or additional meanings are also expanded when I look at new works by artists that were not known to me before. My learning and my experiences also reshape how I see art and how I perceive it; therefore it affects what and how I look at art, and eventually, what I may wish to acquire.

As you know, I have been buying drawings by Roni Horn over the years. That makes one body of work in my mind. And I will continue to want to see – and possibly buy – her new work when it comes out of the studio. On the other hand, I go through epiphanies such as the discovery of work by artists like Jean-Luc Moulène and Nancy Spero – both seen in one single show at Punta della Dogana in Venice lately– that I had never heard of or seen before. Then, if it is possible and if I find the work available, I buy it without asking myself how such works will affect what is already there, at home. For one way or another, they will make sense, either because they go deeper into an existing field or subject matter, or because they open new avenues of thought and comprehension.

The art collection, as I see it, is by nature always unfinished. Collecting is a process, an intellectual and emotional journey and it is a vehicle for learning purposes. It is a means of coming to know people and their ideas; it is a way to try to grasp humanity, and it can help to make some sense of the world, by acting as a catalyst for questions. It is a tool to get to know how others perceive life on earth and it is also a quest for contemplation and introspection. Last but not least – and very important aspect for me – it is an infinite source of pleasure and joy (I shall remind you, that I mentioned the suffering attached to it in the very beginning of this paragraph).

In another realm, I am part of four different museum purchasing groups. Buying art for museum collections is a quite different thing altogether...

MP: That was put so beautifully, thank you. We will talk about your involvement with museums later, as it’s something I think is important. But let’s stick for a moment with collecting in depth. You mentioned Roni Horn. What triggers you to collect an artist in depth?

JCV: If I discover a profound affinity between the artist’s work and my own quest for meaning, then a moment of epiphany follows; such a state of mind and emotion entices me to follow her or his work. In Roni’s case, I cherish her work very much as a whole, but it is her drawings specifically that bring me close to a state of nirvana on earth, that I otherwise fail to achieve through meditation or orgasm. [Laughs.]

An element that needs to be present for me in a work of art is an inherent density or quality to take the observer somewhere else: further, beyond the unknown, beyond the familiar – to put you in contact with the Other.

MP: I understand. And on a related note, is it important for you to know the artist personally? Does having a relationship with an artist affect your relationship with their work in any way?

JCV: Look, there are great artists that have difficult personas, and there are great ones that are sublime to spend time with. It does have an effect on me, but not on the artwork. Yes, I definitely prefer to have a good relationship with the artist, but it is not a pre-condition to enjoy the work –neither to acquire it – by any means.

MP: What you say about collecting artists in depth is very interesting. It’s definitely true that personality does not correlate with the quality of an artwork. I know that your relationship to museums is important to you. You are on the board of several international museums. Why is this important to you, and in what sense does it extend your involvement with contemporary art?

JCV: Collectors should feel the urgency to act towards a common cause and should put themselves at service of their local museums – and their favourite ones. This implies having less private or family museums, which are, with few exceptions, a shot in the wrong direction, unless your last name is Frick or Moreau. I have been repeating this mantra for a long time. Apart from MALI in Lima, of which I have been a Trustee since the age of 33, I have been involved with Tate Modern through the Latin American Acquisitions Committee and as a Trustee of the Tate Americas Foundation. A few years ago, I became involved in the newly created Foundation connected to the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid, of which I serve as its Vice-Chairman of the Board. Last but not least, there is Proyecto AMIL, an art platform in Lima devoted to less conventional art practices. Proyecto AMIL acts as an enabler of artistic ideas, publications, residencies, commissions and other things too. This is, for the moment, a more personal project in conjunction with Joel Yoss.

These duties and responsibilities are very important to me because they allow me to serve the local community – in the case of Lima and Peru – and also to be in contact with a wider audience – as through the two metropolitan museums. It also provides a service to the artists and their work in those geographical or cultural spheres. An art museum is, among other things, a platform that brings the public into contact with the work and the ideas of a virtual ensemble of artists. In the case of the contemporary museum, as in a Kunsthalle, you bring together the work of living artist for a public that feels the need to see and experience what these artists think, feel and choose to do.

Of course, all this activity puts me in contact with more and, perhaps the most interesting, artists. And more. It is a vehicle to meet other collectors, curators, gallerists and cultural agents at large, and to enter in a genuine dialogue with them. It is a phenomenal way to enlarge and enhance your circle of human beings. I have got to know so many beautiful people through this exercise, and I have come across a few really outstanding ones. I have been exposed to their ideas and I have seen the results of their constructive struggle. I feel so happy to be surrounded by so much talent and humanity! It’s the best thing that has happened to me outside the four walls of my home...

MP: Wow. On a related note, I would love to discuss your relationship to the Lima Museum of Art (MALI). What is the significance of this museum for you? Especially considering that you live in Lima and that it is not one of the major cities for contemporary art.

JCV: This is a very simple question for me to answer. The significance of MALI to me is hefty. It all started in the nineteenth century when a great grandparent of mine came from Lugano in Switzerland to work as a specialist craftsman in the plaster works that are in abundance on the walls inside the building and on its façade. But that is the longer version of the answer...

Let me try to be brief but perhaps more eloquent. I felt that I wanted to belong to MALI because I recognised that there were a group of enthusiastic people with a transcendent mission at work there. The mission was – and is – to bring the magnificent art of the people who have inhabited the territory known today as Peru throughout three thousand years or more to the wider public. Keeping that art properly stored for future generations was simply not good enough for me and other members of this team. We are committed to showing a truly encyclopedic account of Peruvian art in a meaningful way. On another note entirely, we also wanted to provide Limeños with a good view of what was, in artistic terms, happening outside the city limits.

Following extensive renovation work, the second floor is now open (4500 sq metres). The collection consists of 17,000 pieces of Peruvian art from all times and in all media, from textiles to video, and from objects in gold and silver to plastic.

MP: What an incredible mission statement. I’d like to return now to your collection. And I have two questions– is there a work that epitomises the point where all your key interests converge? What are these themes?

JCV: Good question! You are asking me whether there is a Gesamtkunstwerk in my collection... [Laughs.) I can respond with many examples, not just one. Among those examples, there is a work by a Peruvian artist named Morros Moncloa; a work produced in the late fifies. It is a painting, an acrylic on agglomerate wood, and its size is rather big (something like 80cm x 160cm). It is a geometric abstraction, painted in very lively colours, of which Canary yellow predominates.

The shapes in the composition are reminiscent of pre-Columbian geometrical abstraction as found in ancient textiles. But the grammar, the syntax of the forms, is very much a particular language developed by the artist. A work very characteristic of Morros. When Cuauhtémoc Medina, at the time curator for Latin American art at Tate Modern, saw it in my office, he exclaimed: ‘...this is Inca Pop!’ Since then, we’ve called it by that name.

It is a work that speaks directly to my nerve. This often happens to me with art that is so powerful – I cannot explain why it is so special. Or is it that I prefer not to talk about it? As if by doing so, I could break the spell that holds me in its grip? It just leaves me speechless. Sorry to disappoint you, this is an interview after all [laughs].

MP: Can you talk about a work in your collection that has a particularly interesting back story? Such as where or how you acquired it?

JCV: You are looking for anecdotes now. I still remember vividly, the thrill I felt when Hester van Roijn bought that Swiss Piece by Donald Judd in a London auction house for me and I was sitting behind her – all because I did not happen to have a paddle.

Of all things material on this world, the thing I regret not beig able to acquire the most is, by far, Donald Judd’s ‘Eichholtern’ (XXXX) on Lake Lucerne in Switzerland. Do you know the site? It was a house, a former restaurant, which Judd transformed into a magnificent piece of perfection by intervening with floors, ceilings, and by knocking down walls and transforming it into a kind of Manhattan-Loft-cum-Swiss-country-house. I was going to purchse it together with a brother of mine and a friend, but as they both dropped out I was left to face a price that was impossible for me at that time. We lost the deal and the house was sold to someone that actually destroyed Judd’s work and converted it into a neo-baroque mansion with no taste or concept. Tragic, isn’t it?